In all likelihood, indeed, the Switch 2 will be backward compatible, meaning it can play games from previous console generations. However, anyone with an awareness of console gaming history knows that this is not guaranteed. There are several reasons why Nintendo’s record on backward compatibility is inconsistent, as is the case with every console manufacturer. And while the feature has always been near the top of players’ wish lists, it has recently become an expectation — something that would be unthinkable to live without.

Although there are some instances of backward compatibility dating back to the 1980s, in the early years of the console industry, the feature was exceedingly rare. The constant changing of physical features ensured that. It seemed reasonable that your console wouldn’t play the same games because the cartridges didn’t fit in the slot, and indeed, the software distribution format is one of the two main technical barriers to backward compatibility.

The other is how you run the games on the hardware at all, and there are three ways to make it happen. One is software emulation, where a more powerful processor runs a program that allows it to pretend to be an older chip running a years-old game. This was beyond the capabilities of most console chipsets until the 2000s. The second is to simply include a new chipset to run the old games on. While older parts are often much cheaper when their replacements come around, they still add a significant amount to the cost of building a console. The third is to base the new chipset on the architecture of the old one so it can run the games natively, which has only really become feasible with the latest generation of consoles.

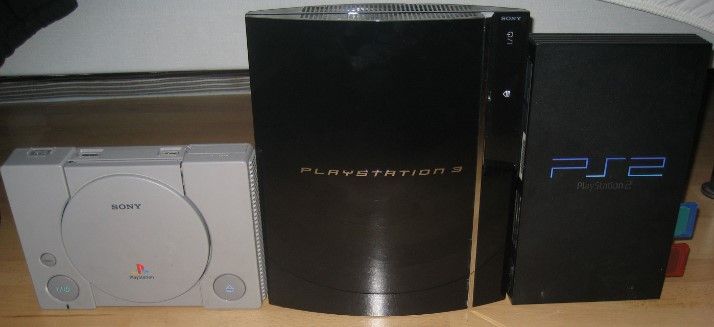

It was Sony that began to change attitudes toward backward compatibility with the PlayStation 2 in 2000. Smartly, its engineers reused the main PlayStation’s processor as a cheap input/output processor, meaning the newer console was able to run PS1 games. The huge popularity of the PS2 made this genie tough to put back in the bottle, but the video game industry sure tried — Sony in particular.

The earliest PlayStation 3s could play PS2 games, but the cost of including PS2 chipsets proved prohibitive, and Sony quickly removed them from subsequent models. However, the design of the PS3 was so complex and unique that it remains almost impossible to emulate to this day, and prohibitively expensive to include as hardware — it’s the lost generation. A reluctance to the feature seemed to come from the top. As late as 2017, PlayStation boss Jim Ryan dismissed backward compatibility as “one of those features that is much requested, but not actually used much,” and when asked about PS2 classics, said, “Why would anyone play this?”

Nintendo’s record on backward compatibility during this period was better — as long as it suited the company’s needs. GameCube games were playable on early models of the Wii, Wii games on the Wii U, and most of Nintendo’s handhelds could play previous generation cartridges. But when the Switch arrived in 2017, Nintendo found itself at a technological impasse. Its emphasis on specific hardware features like dual screens and motion control made backward compatibility, at best, a massive headache, and at worst, a hassle. Coupled with Nintendo’s mission to merge home console and handheld, the company felt that making a clean break from the Wii U and 3DS generation was necessary. Even classic game emulation via the Virtual Console was shelved (though it would eventually return as a benefit of Nintendo Switch Online membership).

However, the prevailing winds in the industry were moving in the opposite direction. Home consoles were now powerful enough to run emulators, while the standardization of distribution formats — first discs, then digital downloads — had removed another barrier. Gaming culture was evolving alongside the technology, too, with less importance attached to novelty and technological advancement, and an increased focus on the preservation and availability of older titles. Under Phil Spencer (who, it must be said, loves old games more than Jim Ryan), Xbox began the arduous task of making the original Xbox and Xbox 360 catalogs available on Xbox One through emulation, game by game. It also promised full backward compatibility for its future — putting pressure on Sony to do the same for the PlayStation 5.

All of this for a feature that is “much requested, but not actually used much”? The Xbox backward compatibility push was great PR, but it was a smart investment in other ways. Spencer had observed that players’ perception of game platforms had changed, largely due to Valve’s Steam. With Steam, the platform was the user account and the library tied to it. The hardware could change, but the library of games remained the same, and this is where players’ investment — both financial and personal — truly lay.

Nintendo’s decision to start from scratch with the Switch proved wise. Its vision of a hybrid handheld system has been immensely popular and is more in line with gaming norms than its previous decade of odd hardware experiments. However, assuming that their next console follows the same format — and reports suggest it will — then extensive, if not perfect, backward compatibility isn’t just a luxury; it’s a benchmark requirement.

People no longer want to stop playing older games, nor are they willing to bid farewell to years of digital purchases that they don’t own as they do boxes on a shelf and that can’t be traded. The Switch has emerging competitors, too, like the Steam Deck and a new generation of handheld computers that provide access to a vast library of games spanning decades. Thanks to the PS5 and Xbox Series X, players are even starting to expect performance gains while playing older games on more powerful hardware.

Getting backward compatibility right on the Switch 2 is not only daunting for Nintendo. It will also require the Kyoto company to preserve some of its deepest instincts. This is a company that has long benefited from rehashing, repackaging, and rereleasing its back catalog in brand new versions. Perhaps the best example is Mario Kart 8 Deluxe, a port of a Wii U title that is now one of the best-selling games of all time. This is a company that has also consistently placed a premium on hardware innovation and gimmicks, and it will need to rein in that temptation and deliver a budget design to ensure compatibility with the Switch library.

Fortunately, there are strong indications that Nintendo’s management team knows this, from reports of the Switch 2’s organic design to a comment from company president Shuntaro Furukawa emphasizing the importance of Nintendo Records in providing “a smooth transition” to the future. But for all that backward compatibility is now taken for granted as a feature, implementing it is a non-trivial challenge, and execution is key. Sitting on 140 million console sales, a large market share, and complete dominance of a niche it created, Nintendo is in a fortunate position as it prepares to launch its next console. But that could be largely undermined if it doesn’t get backward compatibility right.

By Andrej Kovacevic

Updated on 23rd April 2024